Sermon for the Feast of the Epiphany

The text is Matthew 2:1-12.

When I was younger, I used to believe that there was one specific right way, and a whole lot of wrong ways, to practice spirituality. I thought I had to believe all the right doctrines and follow all the rules perfectly, or else God would get mad at me and punish me accordingly.

Now, to be fair to my younger self, there were a few upsides to this way of thinking. For one, it gave me a very strong moral compass, which is a good thing for a young person to have. And number two, it gave me a strong sense of community with others who were trying to practice their spirituality in the same way. And that’s also a good thing.

The downside, however, was that I lived with a constant sense of dread—that if I asked too many tough questions, or failed to live up to my moral code, I would be in deep yogurt with God, who watched everything I did, listened to every word I said, and knew every thought I thunk, and was keeping a meticulous record of all of it, for which I would one day have to answer.

I knew very well just how much I failed to live up to the high standard I set for myself, and I figured that God was looking at me in just the same way—only more so, because God could never forget.

I’ll be honest. Living with that kind of fear, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, was crazy-making. I was told that I needed to trust in God, but the God I believed in—the all-seeing and all-knowing micromanager—wasn’t trustworthy. That kind of God was less like the lover of our souls and more like an abusive ex-boyfriend. No matter how hard I tried, nothing I did would ever be good enough.

I believed these things about God because I thought that’s what it said in the Bible. But then I made one fatal mistake: I actually read the Bible. And what I found there was something more complex, more nuanced, and more loving than the abusive ex-boyfriend I had been in a relationship with up to that moment.

It’s funny, isn’t it, how the Bible is a central source of our theology, but actually reading it can completely wreck that theology?

The gospel for the Feast of the Epiphany is one of those biblical passages that absolutely wrecked my theology. But it didn’t just break me down—it broke me open. This story opened my eyes to the reality that God is both bigger and more loving than all my narrow ideas about God.

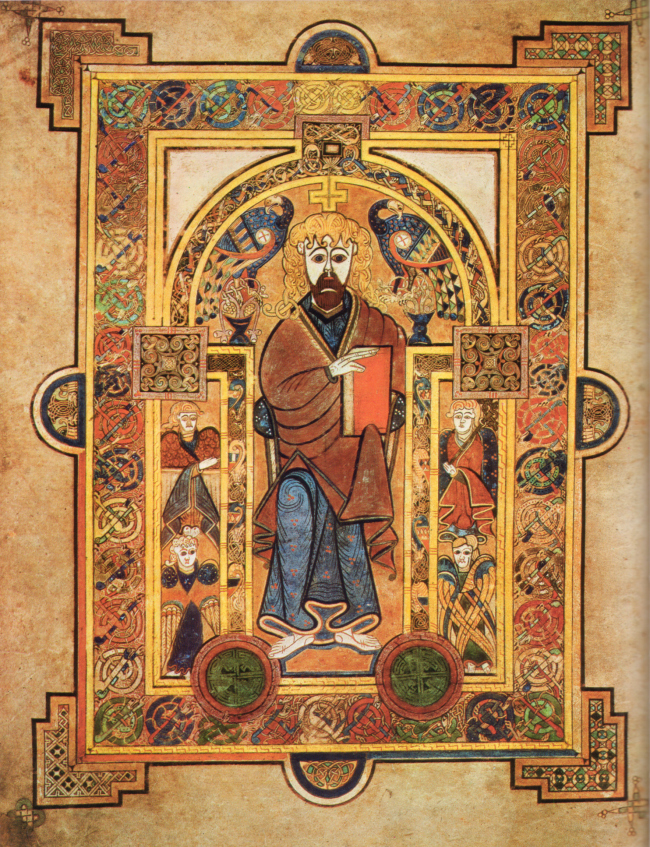

This story—the visit of the magi, or wise men from the East, as our translation renders it—is one of the best-known and least-understood stories in the New Testament. The magi themselves were not Jewish. In all likelihood, they were Persian, from somewhere around the modern-day city of Baghdad in Iraq. The dominant religion in that area at that time was not Judaism, but Zoroastrianism. And these magi were astrologers.

And that’s the first place where the Bible starts to mess with my theology. Because I had always been told that astrology was fake and bad, and that I should stay away from it. But here was this famous story in the Bible, no less, where spiritual seekers are using astrology to find their way to the presence of Jesus. That made me go, wait, what?

And it didn’t stop there. It gets weirder—so hold on to your seats.

These Persian astrologers determined, by practicing their craft, that a great king was being born in the land of Judea, so they figured they should go and pay their respects. And if you’re looking for a newborn king, where else would you go except to the king’s palace in the capital city, right?

So they ring the doorbell and say, “Hey, congratulations.” And King Herod is just standing there like, “What? There’s no newborn king here. What are you talking about?” So he goes and consults with the bishops and the theology professors, and they tell him, “Yeah, it’s not happening here. It’s supposed to happen in Bethlehem, according to the ancient prophecies.”

So Herod sends the magi back out to find this new king—not because he wants to pay his respects, but because he wants to eliminate any possible threat to his power. But the magi don’t know that. So they set out again.

And another really interesting thing happens. The text of Matthew’s Gospel specifically says that the magi didn’t follow the directions the clergy had given them from the Bible. It says that they set out, and they saw the star again, and they followed that instead—and lo and behold, it led them to the exact same place the clergy had told them to go.

They weren’t following the “right” way that was prescribed by the Bible. They were following the light they knew, and it led them to the same place.

It’s hard to be a fundamentalist when you actually read the Bible.

So they get there, to the presence of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. They pay their respects. They offer their gifts. And just as they’re getting ready to go home, they have a dream. And in this dream, God warns them not to return to Herod, but to return to their own country by another road.

Other translations render this sentence as “they went home by another way.” And I really like that turn of phrase.

The magi were going home by another way—not just at the end of the story, but the whole way through. They were not members of the God Squad in the traditional sense. And they didn’t follow the guidance of the Bible. They walked by the light of their own star and ended up exactly where they needed to be anyway.

That says something to me about the God we believe in today—not the abusive ex-boyfriend god, not the all-knowing micromanager, but one who is not afraid of people who ask questions, make mistakes, and travel by their own light. God was with the magi in ways that broke the rules. And that same God is still with us today and has been all along.

One of the many things that I love about the Episcopal Church is that we have a theological tradition where diversity is baked in. Our theology is not about obedience to a single infallible authority. It’s an ongoing dialogue between scripture, tradition, and reason. There is room in our theology for differing viewpoints, and the God we believe in is bigger than all of it.

No book or person or institution is capable of having the last word, because we believe that word hasn’t been spoken yet.

Like the magi, God is still guiding us closer to the presence of Jesus by many and various paths. So none of us has the right to pass judgment on another, or say with absolute certainty, “You’re wrong, and I am right.”

We might think we’re right, but God is usually standing off to the side with a little smirk, going, “Are you sure about that?”

If God could lead the magi to where they needed to be by the light of a star, then surely it’s no big problem for God to lead you wherever you need to be by means of whatever light you follow—no matter the size of your questions, the severity of your mistakes, or the strangeness of your personal beliefs.

Kindred in Christ, that’s the good news of Epiphany for us. What that good news asks of us is the courage to ask the big questions, the humility to make mistakes, and the confidence to trust that we are still loved, even when we don’t get it right.

That is the light that will lead us home by another way.

Amen?