Sermon for the second Sunday of Christmas

The biblical text is Jeremiah 31:7-14.

Sermon recording:

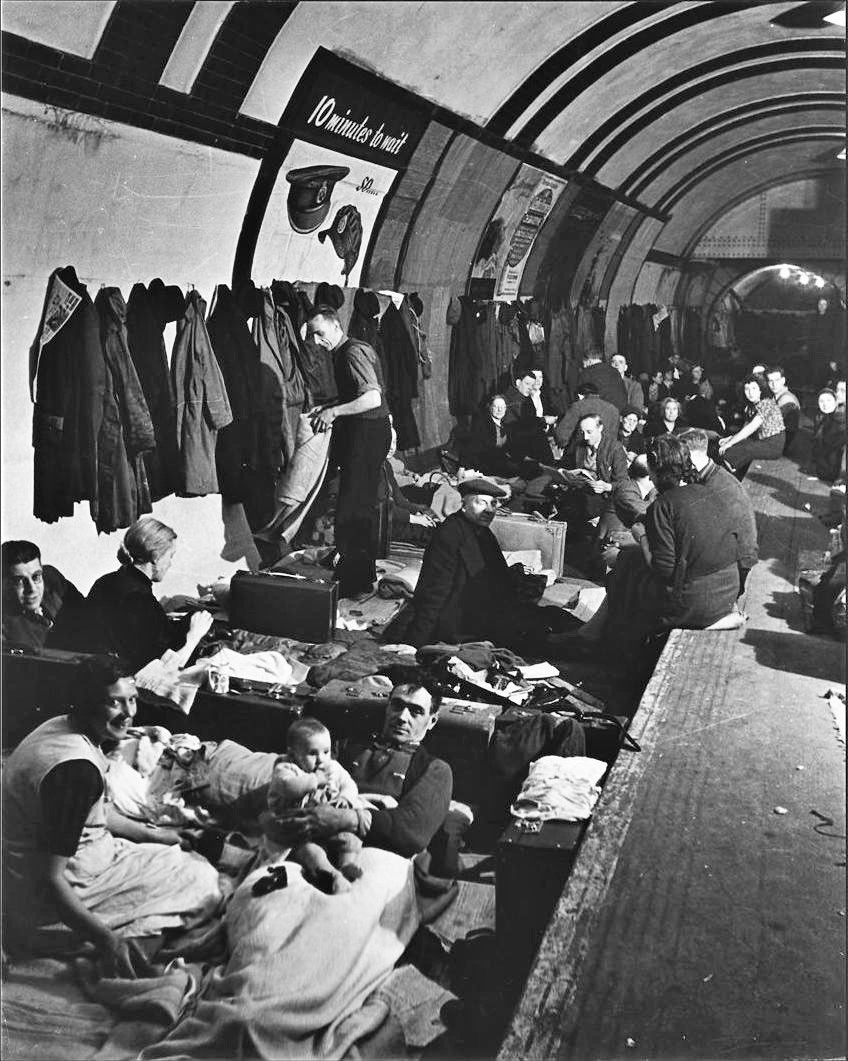

In September 1940, at the height of World War II, the German Luftwaffe began a sustained bombing assault on the British capital that eventually became known as the London Blitz.

As the city burned above them, the people of London gathered and slept in the underground subway tunnels for safety.

And yet, even as the city was being bombed night after night, something remarkable happened: Concerts continued, drama troupes put on plays, teachers taught classes, and an inter-shelter darts league formed. One pianist, Myra Hess, organized daily concerts at the National Gallery. People would come on their lunch breaks, not because the war was over, not because things were safe again, but because something in them knew this mattered.

They didn’t sing because the bombing had stopped.

They sang because without beauty, without meaning, without joy, they wouldn’t survive the bombing at all.

And that human instinct — to cling to hope before everything is fixed — is exactly what we hear in today’s reading from the prophet Jeremiah.

This passage comes from one of the bleakest books in the Bible. Jeremiah is not an easy prophet. He doesn’t offer quick comfort. He doesn’t soften his message. He spends much of the book warning his people — the people of Judah — that a crisis is coming.

For the first large section of the book, Jeremiah is doing one hard thing over and over again. He is speaking the truth about his nation’s injustice, exploitation, and unfaithfulness to God’s covenant, even though he knows the king won’t listen. He keeps telling the truth anyway, even though it gets him ignored, mocked, threatened, and eventually imprisoned.

And the truth he speaks is this:

“If we have lost faith in the core principles that make us who we are as a nation, then no amount of wealth, power, or political strategy will be able to shelter us from the consequences of our own actions.”

Jeremiah is not speaking as an outsider. He is speaking as a concerned citizen. He loves his people. That’s why he tells the truth.

Later in the book, the tone shifts again. By that point, his warnings have gone unheeded. The moment of truth has come and gone. The disaster Jeremiah spoke about has arrived. Jerusalem has fallen to the Babylonians. The people have been carried off into exile.

So, for Jeremiah and the people of Judah, the question is no longer, “How do we avoid this?”

The question is, “How do we live now that it’s here?”

That final section of Jeremiah is about acceptance — not resignation, but the sober recognition that what’s done is done, and all that remains is to make the best of it.

But right in the middle of those two sections, between the warnings and the acceptance, we get a third section that scholars call the Book of Consolation. Chapters 30 through 33. This is the section where today’s first reading comes from.

What’s striking about the Book of Consolation is that Jeremiah offers hope before the exile is resolved. Consolation comes before acceptance. Not because everything is okay, but because Jeremiah knows that, without hope, the people will not be able to survive what lies ahead.

Listen again to the imagery Jeremiah uses. This is not quiet, private reassurance. This is public celebration. Singing. Shouting. Gathering. Grain, wine, and oil. A watered garden.

And notice who’s invited:

The visually impaired.

The mobility impaired.

Those who are pregnant.

Those in labor.

The people who cannot move quickly. The people who cannot carry much. The people who are exhausted, vulnerable, and easily left behind.

If you step back and picture it, what Jeremiah is describing looks less like a church service and more like a street party.

This is not a party for the strong. This is not a celebration of victory or success. This is a gathering that moves at the pace of the most vulnerable. No one is told to wait until they’re healed. No one is told to come back later when they’re stronger.

Everyone belongs.

Jeremiah even says, “I will give the priests their fill of fatness” — as a priest myself, I’m trying not to take that one personally.

But the most important thing to notice is this: the party happens before anything is fixed.

The exile is still real. The losses are still fresh. The future is still uncertain. And yet — the singing continues.

Just like the music during the Blitz, this isn’t a celebration because the danger is gone. It’s a celebration because without joy, without meaning, people won’t make it through what’s coming.

What’s fascinating is that psychology tells us something very similar.

Viktor Frankl, who survived the Nazi concentration camps, noticed that people didn’t endure suffering because it stopped. They endured because they found a reason to keep going. Meaning came first. Relief came later — if it came at all.

Or as Frankl famously put it, those who have a “why” to live can bear almost any “how.”

In other words, hope comes before acceptance. Without it, people collapse.

Developmental psychology tells us something similar from the very beginning of life. Erik Erikson wrote that hope is the first human virtue, formed not through explanation or reasoning, but through trust.

You don’t argue a baby into trust.

You don’t sit down with a newborn and say, “Now listen here, if you’ll just consider the evidence, you’ll see that you have been fed and changed, that your parents love you very much, and that it’s in everyone’s best interest that you lay down and go to sleep…”

Obviously, you don’t do that. You hold them.

Trust comes before understanding. Hope comes before explanation.

That explains why Jeremiah doesn’t wait until the exile is over to offer hope. He offers it first — because without it, the people won’t survive the truth they’re about to face.

The kind of hope Jeremiah is talking about is not mere optimism or denial, but something tougher.

I read a Tweet online that illustrates this kind of hope perfectly. It was written by someone named Matthew @Crowsfault and says:“People speak of hope as if it is this delicate, ephemeral thing made of whispers and spider’s webs. It’s not. Hope has dirt on her face, blood on her knuckles, the grit of the cobblestones in her hair, and just spat out a tooth as she rises for another go.”

I absolutely love that. That’s the kind of hope you need when you’re living in exile.

And that kind of hope matters not just for us as individuals, but for us as communities.

When communities come under strain, they tend to split into two instincts. Some respond by saying the only faithful thing to do is expose every failure, until there’s nothing left but despair. Others respond by saying the only faithful thing to do is protect what’s good, even if it means refusing to see what’s broken.

Jeremiah refuses both extremes.

He loves his people too much to flatter them — and too much to abandon them.

That’s why hope comes first. Accountability without hope turns into cynicism. Hope without accountability turns into denial. Jeremiah offers hope not to erase the truth, but to make it possible for the people to face it.

And this isn’t just about nations or communities. It’s about individual lives, too.

I once read about a mother whose child was born with a severe and terminal disease. There were no long-term plans. No grand ambitions. None of the milestones people usually imagine for their children.

From the outside, many would have called that situation hopeless.

But the mother wrote about discovering a different kind of hope — not hope that things would be different, but hope rooted in love, presence, and fierce attention to the life in front of her. She described learning to delight in small moments, celebrate what was real, even though the future looked nothing like what she had imagined.

That’s the hope Jeremiah is pointing toward.

Not hope that skips over suffering.

Not hope that waits for everything to be resolved.

But hope that shows up anyway — and holds us together while the story is still unfinished.

The music during the Blitz didn’t stop the bombs. But it reminded people who they were.

Jeremiah’s street party didn’t end the exile. But it reminded the people that their story wasn’t over, that God wasn’t done with them, that life itself still carried the possibility of renewal.

So the invitation in this passage is not to pretend that everything is fine. It’s to accept the fact that things are pretty messed up and practice hope anyway. To create moments of joy. To notice what is good and celebrate what is being born, even though the ending is still unclear.

Kindred in Christ, as you look around at our troubled world today, gape in horror at the latest news reports, and wonder what it’s all coming to, I dare you to practice hope as a spiritual discipline.

Not a vague optimism that everything will work out fine, not a distraction from the real problems that we are facing, but a defiant commitment to keep hoping in the face of despair. An unshakable faith that God is not done with us yet, so we owe it to ourselves and each other to keep holding on and keep looking for opportunities to do what good we can, where we can, with whomever we can, and for as long as we can.

Like the people who lived through the London Blitz, we too have a need to sing before the war is over.

We too have a need to gather before the exile ends.

We too have a need to hold tightly onto one another, not because everything is okay, but precisely because it isn’t!

Because hope isn’t what comes after we heal the world.

Hope is what makes healing the world possible.

Amen?