Sermon for the Second Sunday of Easter.

The biblical text is John 20:19-31.

Once upon a time, there was an expecting mother. In her womb, there were twins. These twins, as people often do when they spend a lot of time together, liked to talk about various things. One day, a particularly philosophical question came up. One turned to the other and asked, “Do you believe there’s any such thing as life after birth?”

“Never really thought about it,” the other twin said, “but I highly doubt it. We’ve never seen anything outside of this place. No one who leaves ever comes back. I think that, when the time comes for us to be born, we just go through that passage and cease to exist.”

“I disagree,” the first said, “I mean, you’re right that we’ve never seen anything outside of this place, but just look at these eyes, ears, hands, and feet that we’re growing! Why are we growing them, if we’re never going to use them? I bet, after we go through that passage, we’ll find out there’s a whole world outside that we’ve never seen before. I have no idea what it will be like, but I have a hunch our time in this womb is getting us ready for whatever comes next.

“That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard,” said the other. “I bet the next thing that you’re going to tell me is that you’re one of those crazy religious people who believes in the existence of Mom!”

“Well, I don’t think I’m crazy,” the first said, “but, as a matter of fact, I do happen to believe in Mom.”

“Oh, really?” The other said, “Then why don’t you enlighten me, if you’re so wise? I’ve been in this womb for almost nine months, but I’ve never seen a ‘Mom’ or any evidence that convinces me to believe there’s any such thing as life after birth. So then, just where is this hypothetical ‘Mom’ that you supposedly believe in?”

“It’s hard to explain,” the first said, “but I think that Mom is everywhere, all around us. Everything we see in this womb is a part of Mom. So, I guess, it’s kind of like… maybe we’re growing inside of her? You said you’ve never seen Mom, but I think we’ve never seen anything other than Mom. I don’t pretend to have the answer, but I suppose it’s just another one of those things we won’t know for sure until after we’re born.”

There are two things I’d like to point out about this little parable, which I have adapted from Catholic priest and author Henri Nouwen. First of all, neither twin in the story is in a position to know, with any certainty, what the full truth of the matter is. The answers to questions about “life after birth” and “the existence of Mom” are pretty obvious to you and me, who have lived outside the womb for most of our existence, but we can imagine how scary it must have been when we were going through the process for the first time. Even now, uncertainty about “life after death” and “the existence of God” makes us nervous. Maybe someday in eternity, we’ll look back on our earthly lives and laugh at how little we knew back then, but today we can only know what we know, which might give us a little sympathy for those unborn twins and their philosophical questions.

The second detail from that story I’d like us to notice is that the presence of doubt has absolutely no bearing on the twins’ status as beloved children of their mother. She will love them just the same, no matter what philosophical conclusions they draw during their time in utero. In the same way, even the oldest among us are still babies in the eyes of God. Our eternal Mother knows full well that human beings are incapable of answering the biggest questions about reality, so she is able to have sympathy for those who struggle honestly with doubt. Just like those babies in utero, each and every one of us will be loved forever, no matter what we come to believe during our brief time on this Earth.

This means that doubt is not a barrier to faith.

This second fact about Nouwen’s parable of the twins is what I want us to keep in mind, as we turn to look at today’s gospel.

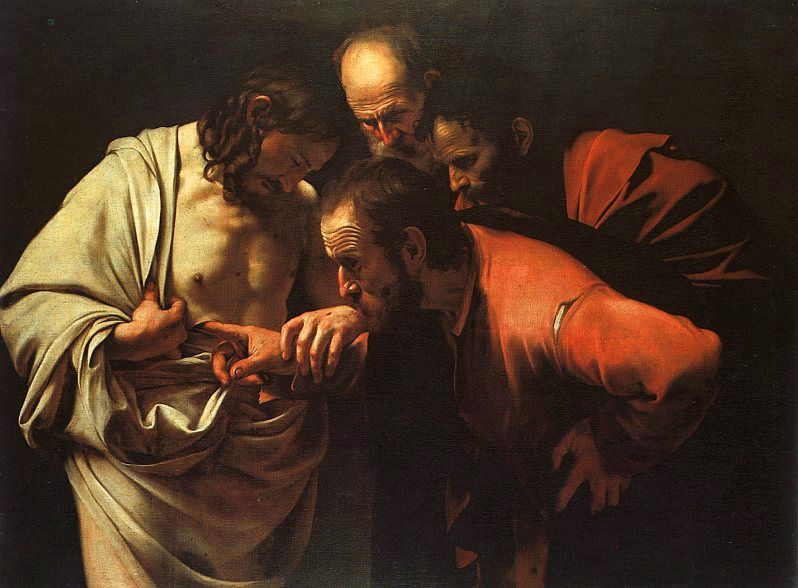

The story of St. Thomas’ encounter with the risen Christ is the most thorough treatment of doubt in the New Testament. Our brother Thomas gets an unfair shake when we use his name to make fun of someone for being “a Doubting Thomas.” After all, Thomas was only doing what any of us would have done, if someone came to us with news that seemed unbelievable. For this reason, I like to think of Thomas as “the patron saint of critical thinkers.” The scientist Carl Sagan famously quipped that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” I imagine Dr. Sagan applauding when St. Thomas proclaims, “Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.”

The most intriguing aspect of this story is not Thomas’ doubt, but Jesus’ response to it. If John’s gospel had been written by modern Fundamentalist Christians, they probably would have said that Jesus couldn’t appear in the upper room until the other disciples had excommunicated Thomas for his skepticism. If Jesus appeared at all, it would probably be on the far side of the locked door, shouting about how Thomas is a “sinner” and is “going to hell,” if he doesn’t change his mind. But that’s not what actually happens in John’s gospel.

In the real version of the story, the text says, “Although the doors were shut, Jesus came and stood among them and said, ‘Peace be with you.’” Thomas’ doubt, for Jesus, was not a reason to stay away, but a reason to come closer. Thomas’ doubt, for Jesus, was not a reason to offer words of judgment, but a reason to offer words of peace. Jesus doesn’t command Thomas to have blind faith, but gives him the extraordinary evidence he’s looking for.

The presence of this passage in our sacred Scriptures should shape the way we deal with doubts, both our own and those of others. It should help us learn how to accept the process of critical thinking as a necessary part of faith. It should lead us, not to retreat from hard questions, but to advance alongside them.

As Episcopalians, we are blessed with abundant spiritual resources to help us on this journey. The Episcopal Church is part of the Anglican theological tradition. One of the things that makes Anglicanism distinct from some other expressions of Christianity is the way in which we think about our faith. Some other churches see their faith as a monolithic statement by a single and infallible authority. For Roman Catholics, it’s the Pope; for Fundamentalist Protestants, it’s the Bible. But the Anglican theological tradition, as far back as Fr. Richard Hooker in the 17th century, has always viewed Christian theology as a three-way dialogue between Scripture, tradition, and reason.

This way of thinking about our beliefs, sometimes called “the three-legged stool,” means that Episcopalians see our religion as a never-ending conversation. Everyone gets to have a seat at the table, but no one gets to stand on the table and yell at everyone else. Unlike some other religious traditions, Episcopalians do not view their leaders as infallible. We honor our ancestors, but we also believe the Church can be wrong. An interpretation that made sense at one time might stop making sense for future generations. A way of life that seemed just and holy in one century might seem abhorrent in another, and vice versa. This doesn’t mean that “anything goes” in Christian faith and practice, but it does mean that Episcopalians are always open to having a conversation about it.

This understanding of the Christian faith means that Episcopalians can be notoriously hard to pin down when someone asks what our church believes. We frequently disagree with each other, sometimes passionately. The late comedian and devout Episcopalian Robin Williams once said, “No matter what you believe, there’s bound to be an Episcopalian somewhere who agrees with you.”

Finally, thinking of the Christian faith as a three-way dialogue between Scripture, tradition, and reason means that The Episcopal Church is a place where you can bring your whole self to church: Protestant and Catholic, conservative and liberal, believer and skeptic. To all these parts of ourselves and each other, the sign outside our churches around the country proclaims the message loud and clear: “The Episcopal Church welcomes you!”

Whoever you are, whatever you believe, however you identify, and wherever you are on your spiritual journey, you are welcome in this sacred space. That is the message that Jesus proclaimed to St. Thomas in today’s gospel. That is the message that The Episcopal Church seeks to embody every day, as it has for hundreds of years. And that is the message that I hope you hear in this sermon today: That you, with all your doubts and fears, are still a beloved child of God, and you are welcome in this place.

Amen.