A few years ago, there was a big to-do about this book (and subsequent movie), The Da Vinci Code. I won’t get into the particulars of the plot, suffice to say that it provoked a lot of big, emotional reactions from people everywhere.

On the one hand, a lot of church-folks were offended by the ideas it presented, which didn’t exactly mesh with what we had learned as kids in Sunday School. On the other hand, a lot of folks from outside the church were really excited about the book because they thought it revealed a picture of Jesus that was bigger than the one presented by traditional Christianity.

I even had one friend who said, “I knew it! The Vatican has known about this stuff all along, they’ve just kept it hidden and locked up in some secret vault so that the rest of us won’t find out about it.”

Well, I don’t think I’d put much stock in that particular theory… or in the book’s ideas about the historical Jesus (The Da Vinci Code is a work of fiction after all), but I do find the whole phenomenon extremely fascinating from a sociological point of view.

During the peak of the book’s popularity, Jesus Christ was once again on the cover of popular, secular magazines. Books were being written (and read) about him. For a brief cultural moment (and not for the first or the last time), everyone was talking about who Jesus is and what he means to the world. It was a really interesting thing to behold.

And here’s what stood out to me in that conversation:

People feel drawn to Jesus. They want to be connected to him somehow, even if they never darken the door of a church or call themselves Christians. Jesus means a lot to people. There are few, even in the non-religious world, who speak negatively about Jesus or the things he said and did. Most secular criticism is directed, not at Jesus himself, but at us Christians (and what we have done in his name).

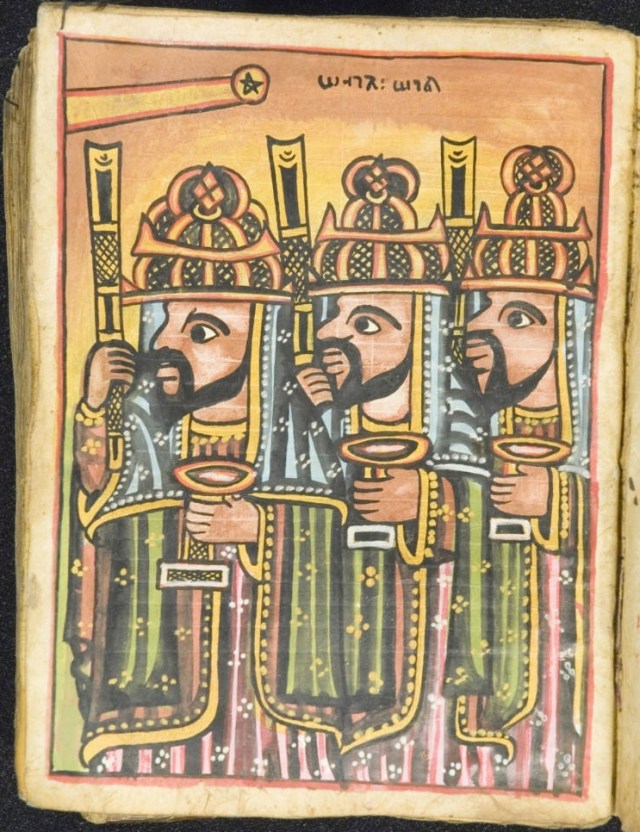

In this morning’s gospel reading, we read about a group of people, the wise men, who also felt drawn to Jesus. Like the readers of The Da Vinci Code, these people came to encounter him from outside the bounds of conventional, orthodox, institutional religion.

In the time of King Herod, after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, asking, “Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews?”

To begin with, these wise men were not Jewish. The text of Matthew’s gospel simply says they were “from the east”, which probably means they came from Persia (the part of the world we now know as Iraq and Iran). They wouldn’t have known anything about the Bible or Jewish customs. They had probably never been to a synagogue service in their life.

So then, how did they come to be aware of this miraculous birth?

“For we observed his star at its rising, and have come to pay him homage.”

They were astrologers. They studied the stars and interpreted their movements as messages from heaven. We have astrologers today who do similar work, but most of it is for entertainment via 1-900 numbers. In the ancient world, astrology was generally accepted as a form of science. Kings and generals would have depended on the predictions of astrologers for guidance.

The message these particular astrologers were discerning from the stars was that something significant was happening in the Jewish homeland. A royal baby was being born. Matthew doesn’t say why, but something in these astrologers’ hearts was stirred enough that they felt compelled to go and pay their respects to the new baby.

So, they did what any reasonable person would do: bring gifts of congratulations to the royal palace in the capital city: Jerusalem. These wise men, Persian astrologers, felt drawn to Jesus, even though they had no idea where to go or what to do when they got there.

King Herod and the Jewish leaders, on the other hand, didn’t fare much better. Even though the astrologers had gotten a little turned around, at least they were aware that something important had happened. The astrologers’ arrival woke the Jewish leaders up to what they had forgotten or neglected in the midst of their own self-important agendas.

“When King Herod heard this, he was frightened, and all Jerusalem with him; and calling together all the chief priests and scribes of the people, he inquired of them where the Messiah was to be born.”

The astrologers’ questions sent the theologians and seminary professors scrambling for answers. As it turned out, the answer they were looking for was in a tiny, little, forgotten village:

“They told him, “In Bethlehem of Judea; for so it has been written by the prophet: ‘And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who is to shepherd my people Israel.'”

The arrival of these outsiders and their questions woke the Jewish religious scholars up to those parts of their own country and their own faith that they had neglected for too long. At this point, Herod and the religious leaders have an opportunity before them. Their eyes have been opened to the Messiah’s birth. They now have the chance to step outside their own selfish, little worlds and become part of what God is doing on earth. Is that what they do?

“Then Herod secretly called for the wise men and learned from them the exact time when the star had appeared.”

Instead, there is a reactionary pushback against this news of the Messiah’s birth. The powerful ones are secretly plotting and scheming, not so that they can be part of what God is doing in the world, but so that they can keep their power and maintain their privileged positions in Israel. Those who have power want to keep it, even if that means going against the very essence of what defines them as a people. They would do anything, even kill the Messiah, to maintain their illusion of power and control.

Herod is so delusional, so drunk with power, that he even starts ordering these foreign wise men around like they were his own subjects or property:

“Then he sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search diligently for the child; and when you have found him, bring me word so that I may also go and pay him homage.””

The irony here is that he is the one who is dependent on them. He would have no knowledge of this situation if it wasn’t for their pagan, foreign practice of astrology. Yet the wise men are the ones who respond with open hearts and minds. They came to pay their respects because they felt drawn by the heavens. All these secret, back-door deals combined with biblical hermeneutics and seminary professors probably seemed pretty strange to them. In the end, it seems like they (rightfully) disregarded everything Herod and the religious scholars had just taught them:

“When they had heard the king, they set out; and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen at its rising, until it stopped over the place where the child was.”

Does the text say that the wise men set out to follow the biblical scholars theologically correct directions? Or does it say that they went back to following what they already knew?

The answer is the latter, of course. The wise men basically took the Bible and theological training and threw it out the window. They didn’t know about all that Jewish stuff, nor did they want to. They knew about stars. So, when they set out again (probably more confused than when they arrived), they went back to working with what they knew.

One might think that such pagan backsliding would lead the wise men down the path of sin and deception. Surely, they would be lost forever in the desert, never to find the newborn king.

But that’s not what happened. The text tells us that the star “stopped over the place where the child was.” Get this: by following what they knew, they ended up exactly where they were supposed to be.

They set out on this journey in search of Jesus, and lo and behold: they found him (in spite of the so-called ‘advice’ given by powerful figures and religious leaders). And what was their reaction when they found him?

“When they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy.”

Their hearts were more open than the hearts of those who had spent their lives studying this stuff.

“On entering the house, they saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage.”

Despite their unorthodox methods and status as religious outsiders, the wise men ended up exactly where they were supposed to be: with Jesus. Their faith did not look anything like conventional Jewish faith, but it proved to be more real and more authentic than the faith of those people who were supposed to have all the answers.

I wonder whether the same thing might be true in the world today?

It seems to me, based on what I saw during The Da Vinci Code’s popularity, that there are a lot of people in this world who feel drawn to Jesus, but want nothing to do with the church or institutional Christianity. To be honest, I can’t blame them. We Christians have a lot to repent for when it comes to representing Jesus to the world. We have often attached his name to our own projects and agendas, but rarely have we acted in a way that is consistent with his Spirit. I think that is what it really means to “Take the Lord’s name in vain”: When we talk about him, but don’t act like him.

Meanwhile, those wise souls who are diligently searching for truth and love in Jesus are driven to look elsewhere because the church has done such a poor job of pointing the way to him. In those circumstances, I am not at all surprised that God is willing to reach out take hold of people’s hearts using things like astrology, science, philosophy, or other religions. I have met atheists who have a closer relationship with God than some Christians (even though the atheists would never use that name: God).

The good news in this is that God is willing to reach out to us human beings using any means necessary. As my seminary roommate was fond of saying, “God will broadcast on any antenna you put up.” Only God knows those hearts that truly seek after God. And, as Jesus himself promised: “Those who seek will find”… he never says they have to seek God in a particular way.

The challenge given to us then is this:

Are we open to what God is doing in the world? Are we open to the fact that God might show up in the least expected way, or in the least expected place? When we encounter others who might be seeking God in ways that seem foreign or unorthodox to us, do we have the faith to trust that God is working in their lives (as well as ours) to bring us all to that place where we can worship Jesus together?

Just like the wise men, these outsiders have precious gifts to bring to the table. Will we work with them and help them to open their treasure chests so that these gifts can be offered to Jesus and shared with the world?

God is inviting us Christians to open our hearts, minds, arms, and doors to those outsiders to the faith who bring unconventional gifts to the table and seek God in unorthodox ways. The question that God sets before us is not “Do we approve of them (or their strange methods)?” or even “Do we welcome/accept/tolerate them in our midst?”

The question is: “Will we travel to Bethlehem with them?”

Will we seek Jesus together as companions in life’s journey? Someone else’s journey might not look exactly like yours and that’s okay. Will we be open to the gifts that others bring to the table? Will we let those gifts challenge our structures of privilege and power? Will we let them change the way we think about church and “the way it’s always been” or the way we think it should be done?

These outsiders come to us, not because we have something they need, but because God has led them to us and called all of us to seek Christ together.

So then: Let’s get going.