Sermon for Proper 23, Year C

Click here for the biblical readings.

Navigating the diverse world of religious beliefs can be an enlightening, if tricky, experience, even when one is already an active participant in a particular faith community. Visiting another community for the first time can feel disorienting. Up until last week, I had been to Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox church services. I had visited a synagogue and even served as a guest preacher in Unitarian Universalist services, but until recently, I had never been to a mosque.

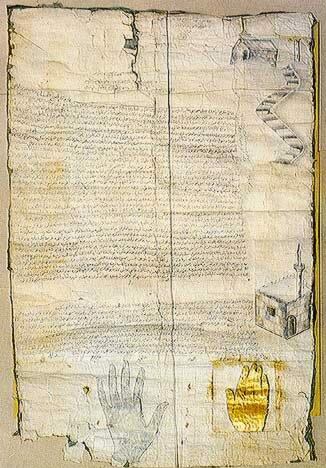

That changed a little over a week ago when I attended Friday prayer services at the American Muslim Society of Coldwater with my friend, Pastor Scott Marsh, of the Coldwater United Methodist Church. Pastor Scott and I meet regularly for mutual support and to discuss joint ministry opportunities in service to the wider Coldwater community.

One concern that we share is for our Muslim neighbors in our beautiful city, most of whom are also Yemeni immigrants. In spite of the fact that there are differences of skin color, religion, and language between these, our neighbors, and the predominantly light-skinned, Christian, and English-speaking population of Coldwater, Pastor Scott and I wanted to send a message of friendship and support from the Christian clergy of this town.

We were concerned that the negative and hostile rhetoric against immigrants and Muslims that seems to predominate in present-day news media was causing our neighbors to feel unsafe and unwelcome in our community. What we discovered instead surprised us greatly, but I will return to that in a moment.

What I want to emphasize right now is the sense of awkwardness that Pastor Scott and I felt as newcomers in a religious space, even though both he and I are trained professionals in the sphere of religion. For once, we did not stride into the room with the confidence of leaders, but with the tentativeness of visitors. We were unaccustomed to the practice of taking off our shoes at the door. We didn’t understand a word of the sermon or the liturgy, which was entirely in Arabic. We were vulnerable outsiders, cut off from the usual trappings of familiarity that make us feel comfortable in the religious spaces where we lead.

This experience of isolation and fragmentation is common in modern society. We, the people of the digital age, for whom the traditional structures of faith and family seem to be eroding away in the relentless stream of data that comes through the internet, are frequently left feeling like strangers in a strange land. We feel cut off from the sources of meaning that sustained our ancestors for generations. In the wake of constant change, this sense of alienation is understandable—and it relates directly to today’s gospel.

In the story that we read this morning, Jesus encounters a group of similarly alienated people. The text tells us that they were lepers, although that term is a bit of a misnomer. Leprosy, in the modern sense, refers to a condition known as Hansen’s disease, but in the ancient world it could refer to one of any number of infectious skin diseases that required those who suffered from them to be quarantined from the general population. Their isolation from the rest of society was not a matter of moral purity but of public health.

The Torah required that people suffering from skin disease keep their distance from everyone else and loudly announce their condition whenever an uninfected person drew near. This was the isolated state of the ten people whom Jesus encountered in today’s reading. Moreover, the reading particularly focuses on one person who was even more isolated than the rest because he was a Samaritan—and thus regarded as a heretic and a half-breed by his Jewish neighbors.

So this person, like many of us in the modern age, was cut off from all the familiar sources that gave life meaning in the ancient world. These ten people, and this one Samaritan in particular, cried out to Jesus for mercy from the depths of their isolation and despair.

Jesus, in turn, reconnected them to the roots of their tradition, where they might find meaning. He said, “Go, show yourselves to the priest.” And the text says that as they went, they were made clean. This was all well and good for most of them, but not for the Samaritan. For him, there was no option of showing himself to the priest because he was not Jewish but a Samaritan, and thus unable to enter the temple and complete the ritual of purification prescribed by the Torah.

So what was he to do? He did the only thing he could think of—he turned around, returned to the presence of Jesus, fell at his feet, and thanked him. Upon seeing this, Jesus asked a very interesting series of questions. He said, “Were not ten made clean? But the other nine—where are they? Was none of them found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?”

I find those to be very interesting questions. Upon hearing them, many of us consider them to be rhetorical questions. The answer, we think, is obviously no. No, no one but this foreigner returned to give praise to God. But that doesn’t sit well with a careful reading of the text.

After all, Jesus had told the ten to go show themselves to the priests, hadn’t he? Presumably, they were doing exactly what Jesus had asked them to do—visiting the priests in the temple and giving thanks to God for their healing, as prescribed in the Torah that their ancestors had followed for generations. The only reason one of them came back to thank Jesus personally was because that person was legally unable to enter the temple under the traditional laws of the Torah.

What I wonder is whether Jesus’s question was not rhetorical but authentic. What if he actually wanted us to consider where the other nine had gone? What if Jesus wanted to show us that there is more than one way to give thanks to God when we are grateful for the good things that God has done for us? What if the diversity of praise is the very thing that Jesus wants to highlight for us in today’s gospel?

Kindred in Christ, I believe that is exactly what is happening in today’s reading. After asking these three poignant questions, Jesus turns to the Samaritan ex-leper and says, “Get up and go on your way. Your faith has made you well.”

The first thing I notice about this sentence is the part where Jesus says, “Go on your way.” It reminds me of the Fleetwood Mac song from the 1970s: You Can Go Your Own Way. He doesn’t tell the Samaritan to convert to Judaism or to start following the laws of the Torah. He says, “You can go your own way.”

And immediately after this, I find it most fascinating that he refuses to take credit for his own miracle. He doesn’t say, “I have made you well.” He says, “Your faith has made you well.” He gives credit not to the giver of the gift but to the receiver. Isn’t that interesting?

To me, that says that Jesus isn’t interested in building a name for himself because Jesus doesn’t have an ego to bruise. I mean, come on—the guy works a miracle and then refuses to take credit for it. Who does that? Only the kind of person who is more interested in helping people than getting credit for it.

Jesus said to the man, “Your faith has made you well.” And there’s something else that’s interesting to me about that. Our translation, the New Revised Standard Version, renders that last phrase as “Your faith has made you well,” but other translations have rendered it differently. Some say, “Your faith has saved you,” or “Your faith has healed you.” But this is one of the very rare instances where I think the 17th-century King James Version actually renders it best. The King James Version says, “Thy faith hath made thee whole.”

And I really like that, because that’s what faith actually does for us. Whether or not faith can cure people of physical ailments or preserve their immortal souls for bliss in the afterlife, faith, we know, has the power to make us whole.

Humans are meaning-making machines. Evolution has hardwired us to look for patterns and connections in the world around us. When we see two unrelated events that seem to be related to one another, we instinctively look for some kind of causal connection between them. We can’t help it—it’s just the way we were made.

Our faith is not a system of beliefs that we cannot prove scientifically, but the means through which we are able to put together the fragmented pieces of our lives into one coherent whole. Like Jesus said to the man in today’s gospel, our faith makes us whole.

Kindred in Christ, that is the good news coming to us through today’s gospel. That is how we can take the fragmented parts of our life and the alienated people in our society and weave them together into one coherent unit—not because we look alike or talk alike or pray alike, but because we have been brought together into one family by the God who loves us all, regardless of our skin color, or ethnic background, or language, or even our religious beliefs. Our faith has made us whole.

When Pastor Scott and I went to the mosque on the Friday before last, we entered that building as strangers and outsiders. We didn’t speak the language. We didn’t share their specific beliefs. And these two white guys didn’t even look like anyone else in that room. But I want to tell you how we received a welcome of radical hospitality and joy and love. We got a tour of the beautiful new facility that they are building for the worship of God and for service to our community.

They spoke to us about members of their faith community who have been in Coldwater longer than either Pastor Scott or I have been on this earth. Kindred in Christ, I want to tell you today, with both embarrassment and joy, that Pastor Scott and I went to that mosque to extend hospitality, but instead we received it. We went there to offer welcome, but instead we were welcomed.

They surrounded us with the loving arms of Allah, which is simply the Arabic word for God. Friends, Pastor Scott and I learned something that day. We discovered, like the Samaritan in today’s gospel, that our faith has made us whole—not an Episcopal faith, or a Methodist faith, or a Muslim faith, but faith in that mystery which transcends all names and categories, including the categories of existence and nonexistence. Faith in God, or Allah, or love, or any other name that you may choose to give this mystery.

It was faith that brought us together. It was faith that united us across the boundaries of our many differences. It was our faith that made us whole.

Amen.